Sometimes I want a painting to be finished, but it just isn’t resolved.

This can happen for any number of reasons:

- a blind spot develops in perception

- willingness to settle for a less than desired outcome

- laziness and creative block

- feeling rushed by pressing deadlines

- dulling of a clear idea

- a demand for greater technical facility

- there is just too much information

In the case of Portrait of Nathaniel Ayers, it was all of the above. It was a good thing that my wife, Caitlin, was willing to address that it wasn’t finished and needed some serious work. Reluctantly, I conceded that she was right.

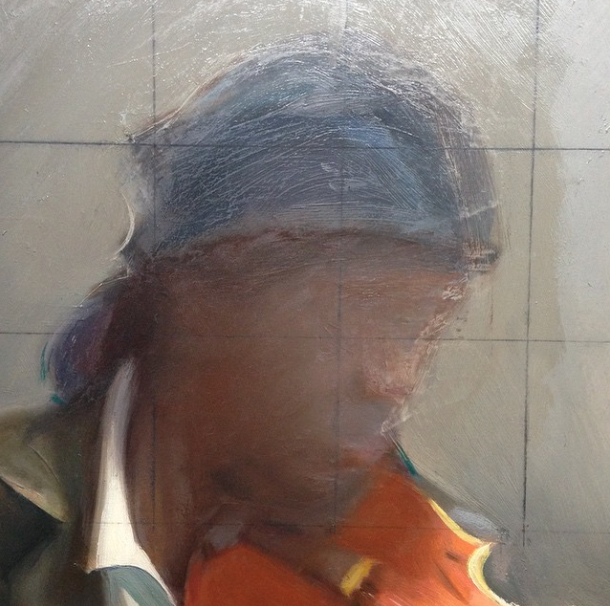

This painting began on a late October evening of 2009. I had seen Nathaniel standing on Los Angeles Street, where I had been renting a studio space. I recognized him and invited him upstairs to sit for me. Nathaniel accepted my invitation and for the next two hours, I painted and photographed him while he practiced fervently. Over time, the portrait seemed to call to my attention from the shadows of my studio. I decided to finish the piece for my third solo exhibition in Los Angeles, Liminal View. The image on the left is a record of the state of the portrait exhibited in 2013. The image on the right is the current state of the portrait nearly eight years after the initial sitting. In my opinion, it captures an intimate moment of intense practice and inward reflection.

A razor blade held perpendicularly can be used to scrape off the painted surface of a portion you wish to rework.

Most of the lower part of the figure, his legs, feet, the violin case and bottle of soda water are left untouched, while the head, torso, hands, violin and background underwent extensive reworking. The most significant changes include the elimination of place, the adjustment of proportions of the head and body, the overall clarification of color and tone in the figure and the simplification of structure and palette of the ground.

Changes in technical application included a site-size method (whereby the source image and the painting are the same size and viewed from the same distance) and the decision to paint from the laptop screen instead of printed digital images. The gridlines were used in the final reworking of the head. I chose to leave them because they reveal the schematic nature of preliminary drawing. This systematic approach and paring down of information is meant to emphasize the constancy in purpose of this gifted American musician.

It is important to have the confidence to admit when something isn’t right, no matter how much time and energy invested. There can be a reluctance to take action to resolve a painting, for fear of overworking, but going too far and learning to come back is a much more valuable lesson than stopping short to be safe.

Portrait of Nathaniel Ayers 2013 (photo credit Brian Forrest); Portrait of Nathaniel Ayers 2015 (photo credit Craig Kirk)